rushdoshi.com

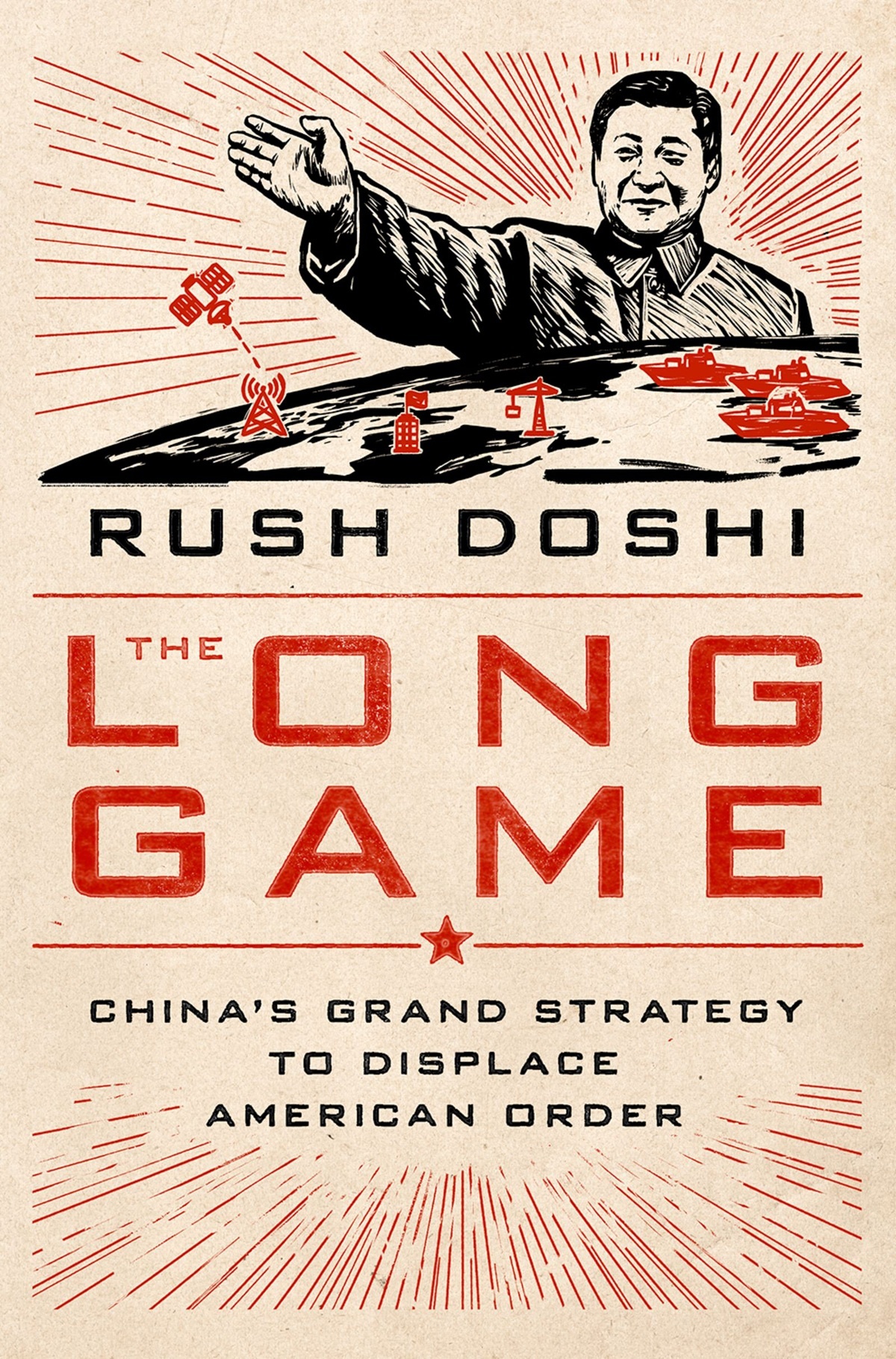

For more than a century, no US adversary or coalition of adversaries not Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, or the Soviet Union has ever reached sixty percent of US GDP. China is the sole exception, and it is fast emerging into a global superpower that could rival, if not eclipse, the United States. What does China want, does it have a grand strategy to achieve it, and what should the United States do about it?

In The Long Game, Rush Doshi draws from a rich base of Chinese primary sources, including decades worth of party documents, leaked materials, memoirs by party leaders, and a careful analysis of China’s conduct to provide a history of China’s grand strategy since the end of the Cold War. Taking readers behind the Party’s closed doors, he uncovers Beijing’s long, methodical game to displace America from its hegemonic position in both the East Asia regional and global orders through three sequential “strategies of displacement.” Beginning in the 1980s, China focused for two decades on “hiding capabilities and biding time.” After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, it became more assertive regionally, following a policy of “actually accomplishing something.” Finally, in the aftermath populist elections of 2016, China shifted to an even more aggressive strategy for undermining US hegemony, adopting the phrase “great changes unseen in a century.”

After charting how China’s long game has evolved, Doshi offers a comprehensive yet asymmetric plan for an effective US response. Ironically, his proposed approach takes a page from Beijing’s own strategic playbook to undermine China’s ambitions and strengthen American order without competing dollar-for-dollar, ship-for-ship, or loan-for-loan.

A bold assessment of what the Chinese government’s true foreign policy objectives are, The Long Game offers valuable insight to the most important rivalry in world politics.

Rush Doshi is the founding director of the Brookings China Strategy Initiative and a fellow (on leave) at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center. Previously, he was a member of the Asia policy working groups for the Biden and Clinton presidential campaigns and a Fulbright Fellow in China. His research has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Foreign Affairs, and International Organization, among other publications. Proficient in Mandarin, Doshi received his PhD from Harvard University focusing on Chinese foreign policy and his bachelor’s from Princeton University. He is currently serving as Director for China on the Biden Administration’s National Security Council (NSC), but this work was completed before his government service, is based entirely on open sources, and does not necessarily reflect the views of the US Government or NSC.

The Long Game

Skip “Acknowledgements”

Read until end of “Why Grand Strategy Matters”

The Long Game: Free E-book preview

![]()

More:

For those not savy, Cambridge Analytica (now renamed as Emerdata Ltd) used ill-gotten data troves, behavioral profiling, ad micro-targeting via Facebook, and Machine Learning to win elections and influence opinions and politics towards a populist, hyper-conservative slant worldwide

economist.com/books-and-arts/2021/07/31/china-aims-to-eclipse-america-by-2049-a-biden-official-writes

As Mr Doshi describes it, the crucible of China’s grand strategy was the “traumatic trifecta”: the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, the first Gulf war of 1991 and, also that year, the collapse of the Soviet Union. These events convinced China that America posed the biggest threat ideologically, militarily and geopolitically. China responded by devising a plan to blunt American power. This was to be low-key: Deng Xiaoping, then retired as a party leader but still highly influential, suggested China should “hide its capabilities and bide its time”. The country focused on developing weapons that would keep America at bay and on joining multilateral organisations such as the World Trade Organisation, hoping to use these institutions’ rules to constrain America.

Then came the financial crisis of 2007-09. According to Mr Doshi, this meltdown convinced China that America was waning and that the time was ripe to start building China’s own power more actively. China began acquiring aircraft-carriers and, under Xi Jinping, who took over in 2012, creating regional institutions to establish a China-centred order. Mr Xi launched the Belt and Road Initiative to help China achieve the same goal globally.

A “new trifecta”—Donald Trump’s winning of the American presidential election of 2016, Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union and the West’s faltering response to the covid-19 pandemic—persuaded China that Western power was in irreversible decline. China decided that, given these and other “great changes unseen in a century”, world dominance could be achieved by 2049, argues Mr Doshi.

There is no conclusive evidence of this. …