bridgewater.com/research-and-insights/tracking-and-assessing-monetary-policy-3-around-the-world

In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, we have built out our framework for understanding economic policy going forward: what we call Monetary Policy 3. In short, with interest rates around the world at zero and traditional methods of monetary stimulus now ineffective, policy makers have been forced to turn to coordinated monetary and fiscal policy in order to engineer any hope for a sustained recovery. Senior Portfolio Strategist Jim Haskel sits down with Co-CIO Greg Jensen and senior investor Jason Rotenberg to discuss how we’re tracking MP3 implementation around the world, the divergences we’re seeing between countries, and the challenges policy makers are facing.

August 6, 2020 By Greg Jensen, Jason Rotenberg, Jim Haskel

![]()

Subscribe:

More:

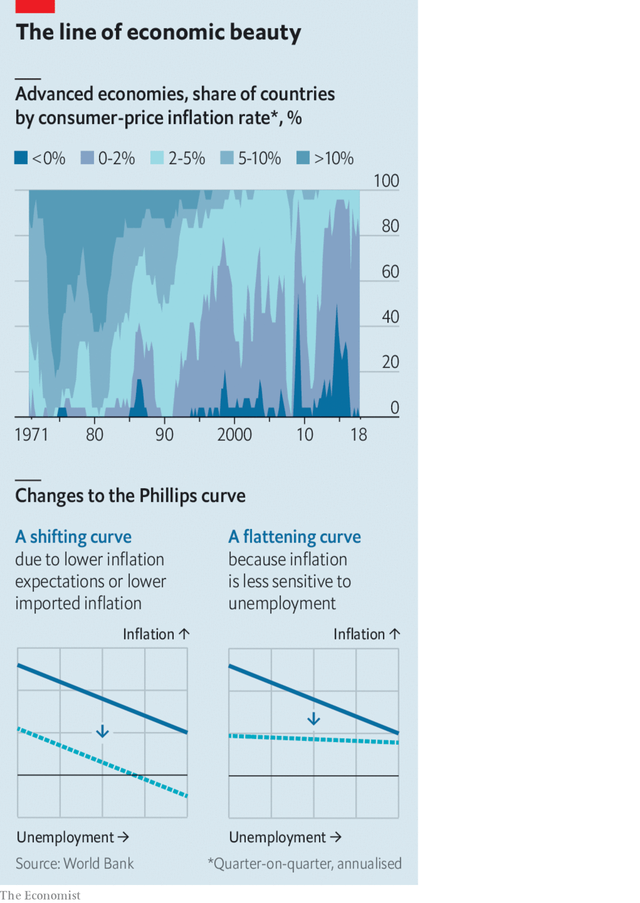

The Philips Curve: Unemployment and Inflation

economist.com/schools-brief/2020/08/20/why-does-low-unemployment-no-longer-lift-inflation

Although the flat Phillips curve puzzles central banks as much as anyone, they may be partly responsible for it. The curve is supposed to slope downwards (when inflation or unemployment is high, the other is low). But central banks’ policies tilt the other way. When inflation looks set to rise, they typically tighten their stance, generating a little more unemployment. When inflation is poised to fall, they do the opposite. The result is that unemployment edges up before inflation can, and goes down before inflation falls. Unemployment moves so that inflation will not.

The relationship between labour-market buoyancy and inflation still exists, according to this view. And central banks can still make some use of it. But precisely because they do, it does not appear in the data. “Who killed the Phillips curve?” asked Jim Bullard, an American central banker, at a conference of his peers in 2018. “The suspects are in this room.”

But what happens when the killers run out of ammunition? To keep the Phillips curve flat, central banks have to be able to cut interest rates whenever inflation threatens to fall. Yet they can run out of room to do so. They cannot lower interest rates much below zero, because people will take their money out of banks and hold onto cash instead.

When Mr Bullard spoke, the Federal Reserve expected the economy to continue strengthening, allowing it to keep raising interest rates. But that proved impossible. The Fed was able to raise interest rates no higher than 2.5% before it had to pause (in January 2019) then reverse course. The neutral interest rate proved to be lower than it thought. That left it little room to cut interest rates further when covid-19 struck.

What do changes in the Fed’s longer-run goals and monetary strategy statement mean?

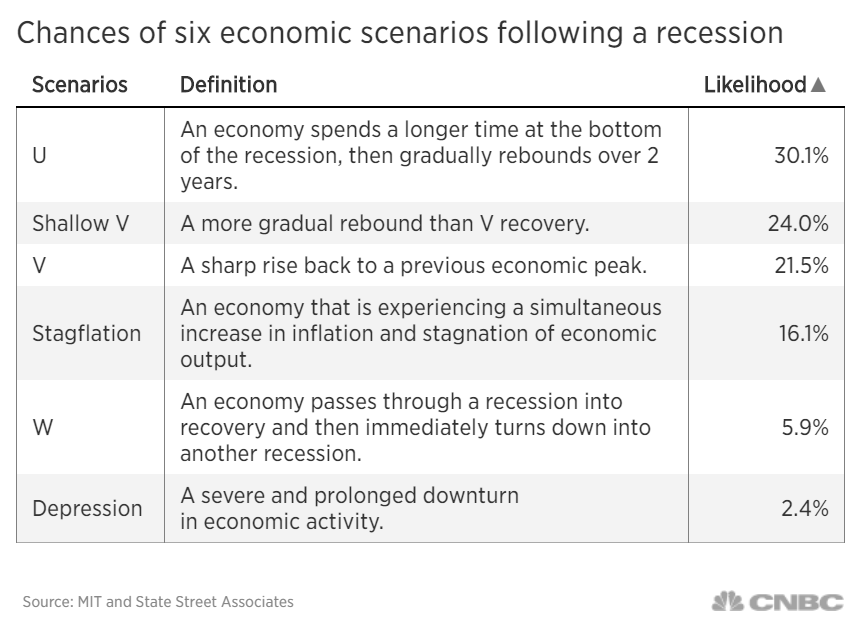

Is Stagflation Next?

cnbc.com/2020/06/24/accurate-economic-research-group-using-math-derived-from-skull-measurements-sees-slower-recovery.html

From “Portfolio Choice with Path-Dependent Preferences“

MIT Sloan School of Managment and State Street Associates

IMF.org/basics

It is a sorry state of the Congress when the Fed passes the baton,

only to say months later that they may end up having to take it back!

Previously:

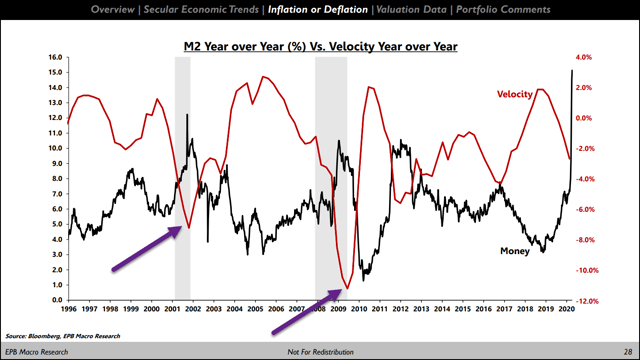

The Inflation vs. Deflation tug-of-war (2020-04-28):

seekingalpha.com/article/4340323-inflation-vs-deflation-tug-of-war