Preface:

Previously, I gave a list of “dead tree” books that I’ve been taking a look at recently.

If websites or information snacking is more your thing, the following are a couple of neat little compendiums and tid-bits:

The best in software writing I:

neilk.net/blog/2005/06/20/links-to-essays-in-best-software-writing-i/

The best in software writing II:

discuss.joelonsoftware.com:80/?bsw

Top ten (Joel on Software):

joelonsoftware.com/category/reading-lists/top-10

Usability testing, integrating user feedback into software design process:

gamespot.com/articles/the-science-of-playtesting

gdcvault.com/play/1566/Valve-s-Approach-to-Playtesting

The Joel Test: 12 steps to better code

Software testing:

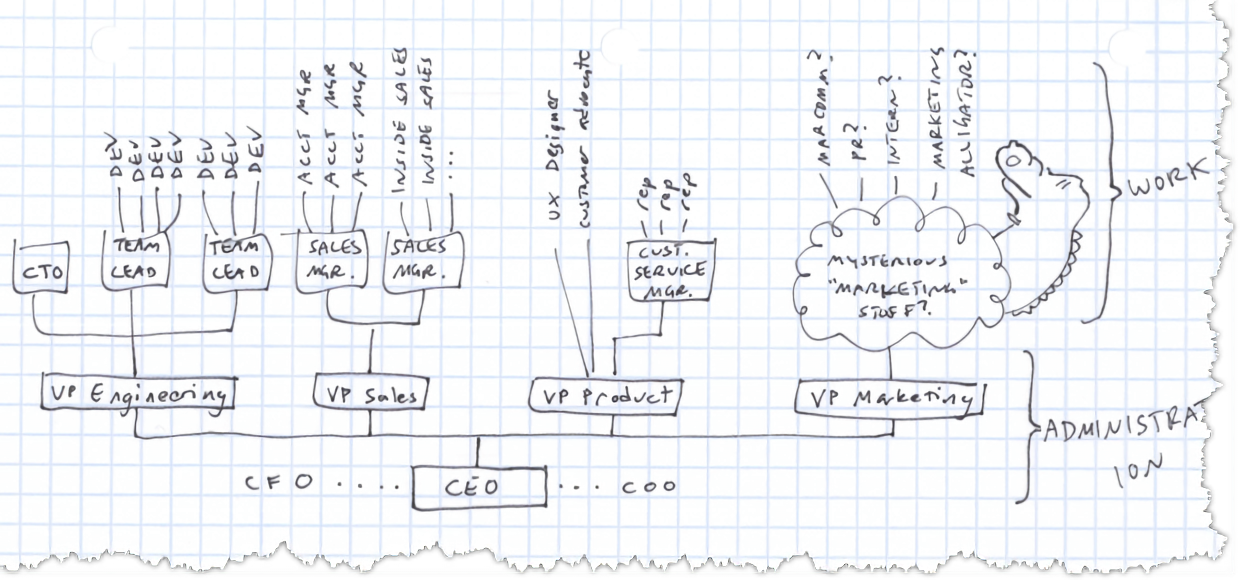

Pushing decisions to the team (lowest possible level):

Devs, workers, etc. are the “leaves” at the top of the tree with the most pertinent information to tasks at hand

Management act as facilitators to identify roadblocks, enhance collaboration, set goals etc.

“move the furniture around”

The saddest thing about the Steve Jobs hagiography is all the young ‘incubator twerps’ strutting around Mountain View deliberately cultivating their worst personality traits because they imagine that’s what made Steve Jobs a design genius. Cum hoc ergo propter hoc, young twerp. Maybe try wearing a black turtleneck too.

…

For every Steve Jobs, there are a thousand leaders who learned to hire smart people and let them build great things in a nurturing environment of empowerment and it was AWESOME. That doesn’t mean lowering your standards. It doesn’t mean letting people do bad work. It means hiring smart people who get things done (+) — and then getting the hell out of the way.

Gaffney knew his top leaders were historically used to a top-down culture. So to facilitate the transition, he has spent a lot of time coaching the company’s management to help them shift toward a bottom-up leadership structure.

“I spend a lot of time with the folks at the top couple layers of the official org chart, just talking to them about what it means to be in service to the folks who are in service to our customers — so in service to them rather than in charge of them,” Gaffney says.

Providing a model for what you want leadership to look like is important in helping people evolve their approaches and buy into the changes. One way Gaffney offered this was by implementing a training program to help people examine different approaches to leading. He also decided to run the program personally. “It’s a leadership development program that is based on reading about leaders in other situations and engaging in a group dialogue of how did those leaders approach the situation, and how did they model the kind of leadership that we’re looking for,” Gaffney says.

“One thing that we’ve done very proactively is to make sure that our club member is always front and center, even if the thing that we’re working on might seem so ‘back-officey’ that you don’t know how it could be connected to the member,” Gaffney says. “So we tell a lot of member stories. That’s a very important part of our culture, is to remind everyone why we’re here.”

Sharing stories about your company helps employees to connect to your customers and your business in a more participative way, because it facilitates a more personal response. “It just seems to work well though because it is a tool that lowers the barriers to having dialogue versus monologue, because people can tell you what parts of a story resonate with them, what parts they have questions about and what parts trouble them,” Gaffney says. “Storytelling just seems to be a medium that unlike PowerPoint, really draws people in.”

Another way to motivate employee participation is to ask more questions. This helps draw out people who may be more reserved in bringing their ideas to the table.

“When you ask folks, they usually have things they want to tell you, but when you don’t ask they generally don’t want to bring them up,” Gaffney says. “It’s the rare individual that will proactively bring up something that they know could be improved. But when you ask them, most people respond to that invitation.”

Gaffney now asks everyone in a leadership role at the company to double their question-to-statement ratio.

(Gen. James Mattis) afcea.org/content/military-needs-new-operational-paradigm

Fifth, training and education play a prominent—if not the predominant—role in command and control and the exercise of commander’s intent, no matter how rudimentary or sophisticated the C2 system. Training and education enable decentralized decision making down to the lowest possible level, and thus allow a reduction in the size of headquarters by orders of magnitude. This will speed decision making, reduce internal frictions and unleash subordinates.

…

Constant feedback loops are the key. Thus, a change in terminology is needed, from “command and control” to “command and feedback.” This is more than a rhetorical change; it is a change in how to think about and conduct operations.

…

Focus on customers, not competitors:

mycustomer.com/community/blogs/colin-shaw/bezos-obsess-over-customers-not-competitors

If you haven’t read Jeff Bezos’ latest letter to his shareholders, put it on your to-do list pronto. There are many takeaways from his letter, but one that stands out to me most is this: “Obsess over customers, not competitors.”

True Customer Obsession

There are many ways to center a business. You can be competitor focused, you can be product focused, you can be technology focused, you can be business model focused, and there are more.

But in my view, obsessive customer focus is by far the most protective of Day 1 vitality.

Why? There are many advantages to a customer-centric approach, but here’s the big one: customers are always beautifully, wonderfully dissatisfied, even when they report being happy and business is great.

Resist Proxies:

As companies get larger and more complex, there’s a tendency to manage to proxies. This comes in many shapes and sizes, and it’s dangerous, subtle, and very Day 2.

A common example is process as proxy. Good process serves you so you can serve customers. But if you’re not watchful, the process can become the thing. This can happen very easily in large organizations. The process becomes the proxy for the result you want. You stop looking at outcomes and just make sure you’re doing the process right. Gulp.

…

Another example: market research and customer surveys can become proxies for customers – something that’s especially dangerous when you’re inventing and designing products

…

Good inventors and designers deeply understand their customer. They spend tremendous energy developing that intuition. They study and understand many anecdotes rather than only the averages you’ll find on surveys. They live with the design.

Embrace External Trends

The outside world can push you into Day 2 if you won’t or can’t embrace powerful trends quickly. If you fight them, you’re probably fighting the future. Embrace them and you have a tailwind. These big trends are not that hard to spot (they get talked and written about a lot), but they can be strangely hard for large organizations to embrace.

We’re in the middle of an obvious one right now: machine learning and artificial intelligence.

Over the past decades computers have broadly automated tasks that programmers could describe with clear rules and algorithms. Modern machine learning techniques now allow us to do the same for tasks where describing the precise rules is much harder

Matt’s opinion: Kubernetes / software containerization appears to me to be one of these trends as well, having clearly navigated the transition from a ‘flavor of the month’ software toolkit into a mature software ecosystem and powerful community.

This ecosystem has democratized the software industry and enterprise IT by making, simple, reliable, and heavily scalable infrastructure available to organizations of all sizes. It has become and likely will continue to be a staple in computing.

High Velocity Decisions

…To keep the energy and dynamism of Day 1, you have to somehow make high-quality, high-velocity decisions.

…

Second, most decisions should probably be made with somewhere around 70% of the information you wish you had. If you wait for 90%, in most cases, you’re probably being slow. Plus, either way, you need to be good at quickly recognizing and correcting bad decisions. If you’re good at course correcting, being wrong may be less costly than you think, whereas being slow is going to be expensive for sure.

…

Fourth, recognize true misalignment issues early and escalate them immediately. Sometimes teams have different objectives and fundamentally different views. They are not aligned. No amount of discussion, no number of meetings will resolve that deep misalignment. Without escalation, the default dispute resolution mechanism for this scenario is exhaustion. Whoever has more stamina carries the decision.

…

“You’ve worn me down” is an awful decision-making process. It’s slow and de-energizing. Go for quick escalation instead – it’s better.

Three management styles (Joel on Software)

The command and control management style

In life or death situations, the military needs to make sure that they can shout orders and soldiers will obey them even if the orders are suicidal. That means soldiers need to be programmed to be obedient in a way which is not really all that important for, say, a software company.

In other words, the military uses Command and Control because it’s the only way to get 18 year olds to charge through a minefield, not because they think it’s the best management method for every situation.

Another big problem with Econ 101 management is the tendency for people to find local maxima. They’ll find some way to optimize for the specific thing you’re paying them, without actually achieving the thing you really want.

That leaves a technique that I’m going to have to call The Identity Method. The goal here is to manage by making people identify with the goals you’re trying to achieve. That’s a lot trickier than the other methods, and it requires some serious interpersonal skills to pull off. But if you do it right, it works better than any other method.

(Shrinkwrap/SaaS) Set your priorities:

joelonsoftware.com/2005/10/12/set-your-priorities/

Shrinkwrap is the take-it-or-leave it model of software development. You develop software, wrap it in plastic, and customers either buy it, or they don’t. They don’t offer to buy it if you implement just one more feature. They don’t call you up and negotiate features. You can’t call up Microsoft and tell them, “Hey, I love that BAHTTEXT function you have in Excel for spelling out numbers in Thai, but I could really use an equivalent function for English. I’ll buy Excel if you implement that function.” Because if you did call up Microsoft here is what they would say to you:

“Thank you for calling Microsoft. If you are calling with a designated 4-digit advertisement code, press 1. For technical support on all Microsoft products, press 2. For Microsoft presales product licensing or program information, press 3. If you know the person at Microsoft you wish to speak to, press 4. To repeat, press Star.”

The five competitive forces that shape strategy:

ibbusinessandmanagement.com/uploads/1/1/7/5/11758934/porters_five_forces_analysis_and_strategy.pdf

hbr.org/1979/03/how-competitive-forces-shape-strategy

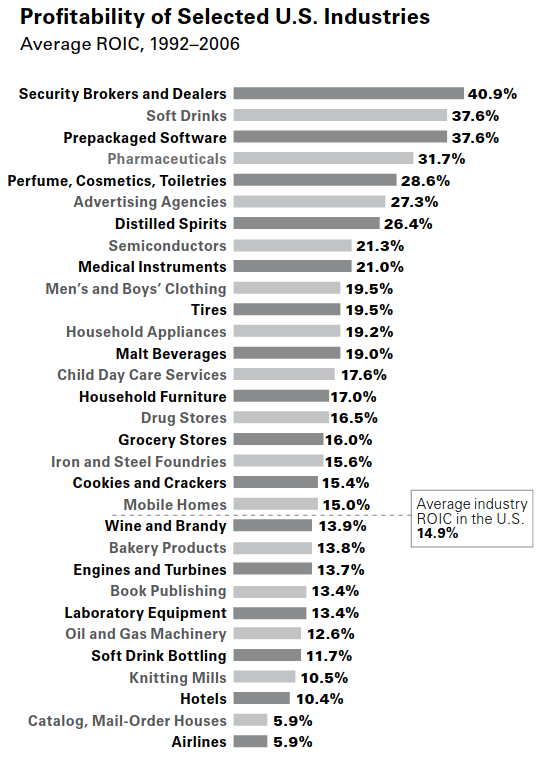

But to understand industry competition and profitability in each of those three cases, one must analyze the industry’s underlying structure in terms of the five forces.

If the forces are intense, as they are in such industries as airlines, textiles, and hotels, almost no company earns attractive returns on investment.

If the forces are benign, as they are in industries such as software, soft drinks, and toiletries, many companies are profitable. Industry structure drives competition and profit-ability, not whether an industry produces a product or service, is emerging or mature, high-tech or low-tech, regulated or unregulated.

…even though rivalry is often fierce in commodity industries, it may not be the factor limiting profitability. Low returns in the photographic film industry, for instance, are the result of a superior substitute product—as Kodak and Fuji, the world’s leading producers of photographic film, learned with the advent of digital photography.

In such a situation, coping with the substitute product becomes the priority.

By understanding how the five competitive forces influence profitability in your industry, you can develop a strategy for enhancing your company’s long-term profits. Porter suggests the following:

• Position your company where forces are the weakest (+)

Strategy Letter I: Ben and Jerry’s vs. Amazon

Building a company? You’ve got one very important decision to make, because it affects everything else you do. No matter what else you do, you absolutely must figure out which camp you’re in, and gear everything you do accordingly, or you’re going to have a disaster on your hands.

The decision? Whether to grow slowly, organically, and profitably, or whether to have a big bang with very fast growth and lots of capital.

The organic model is to start small, with limited goals, and slowly build a business over a long period of time. I’m going to call this the Ben and Jerry’s model, because Ben and Jerry’s fits this model pretty well.

The other model, popularly called “Get Big Fast” (a.k.a. “Land Grab”), requires you to raise a lot of capital, and work as quickly as possible to get big fast without concern for profitability. I’m going to call this the Amazon model, because Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, has practically become the celebrity spokesmodel for Get Big Fast.

Ben and Jerry’s companies start on somebody’s credit card. In their early months and years, they have to use a business model that becomes profitable extremely quickly, which may not be the ultimate business model that they want to achieve. For example, you may want to become a giant ice cream company with $200,000,000 in annual sales, but for now, you’re going to have to settle for opening a little ice cream shop in Vermont, hope that it’s profitable, and, if it is, reinvest the profits to expand business steadily. The Ben and Jerry’s corporate history says they started with a $12,000 investment. ArsDigita says that they started with an $11,000 investment. These numbers sound like a typical MasterCard credit limit. Hmmm.

Amazon companies raise money practically as fast as anyone can spend it. There’s a reason for this. They are in a terrible rush. If they are in a business with no competitors and network effects, they better get big super-fast. Every day matters.

…

Getting big fast gives the impression (if not the reality) of being successful. When prospective employees see that you’re hiring 30 new people a week, they will feel like they are part of something big and exciting and successful which will IPO. They may not be as impressed by a “sleepy little company” with 12 employees and a dog, even if the sleepy company is profitable and is building a better long-term company.

As a rule of thumb, you can make a nice place to work, or you can promise people they’ll get rich quick. But you have to do one of those, or you won’t be able to hire.

…

Still can’t decide? There are other things to consider. Think of your personal values. Would you rather have a company like Amazon or a company like Ben and Jerry’s? Read a couple of corporate histories – Amazon and Ben and Jerry’s for starters, even though they are blatant hagiographies, and see which one jibes more with your set of core values. Actually, an even better model for a Ben and Jerry’s company is Microsoft, and there are lots of histories of Microsoft. Microsoft was, in a sense, “lucky” to land the PC-DOS deal, but the company was profitable and growing all along, so they could have hung around indefinitely waiting for their big break.

Think of your risk/reward profile. Do you want to take a shot at being a billionaire by the time you’re 35, even if the chances of doing that make the lottery look like a good deal? Ben and Jerry’s companies are not going to do that for you.

Probably the worst thing you can do is to decide that you have to be an Amazon company, and then act like a Ben and Jerry’s company (while in denial all the time). Amazon companies absolutely must substitute cash for time whenever they can. You may think you’re smart and frugal by insisting on finding programmers who will work at market rates. But you’re not so smart, because that’s going to take you six months, not two months, and those 4 months might mean you miss the Christmas shopping season, so now it cost you a year, and probably made your whole business plan unviable.

Running a headquarters

The ideal way to run a headquarters is to have one man, preferably over 80, sitting in an office by himself. Anything else is pure frippery.

-Charlie Munger – Becoming Warren Buffett

(a bit tongue-in-cheek)

Net present value

When forced to choose between optimizing the appearance of our GAAP accounting and maximizing the present value of future cash flows, we’ll take the cash flows.

Jeff Bezos, 1997 letter to shareholders

hbr.org/2014/11/a-refresher-on-net-present-value

Most people know that money you have in hand now is more valuable than money you collect later on. That’s because you can use it to make more money by running a business, or buying something now and selling it later for more, or simply putting it in the bank and earning interest. Future money is also less valuable because inflation erodes its buying power. This is called the time value of money. But how exactly do you compare the value of money now with the value of money in the future? That is where net present value comes in.

Vertical and Horizontal Integration:

In the first gilded age, Rockefeller’s Standard Oil:

Standard was growing horizontally and vertically. It added its own pipelines, tank cars, and home delivery network. It kept oil prices low to stave off competitors, made its products affordable to the average household, and, to increase market penetration, sometimes sold below cost. It developed over 300 oil-based products from tar to paint to petroleum jelly to chewing gum. By the end of the 1870s, Standard was refining over 90% of the oil in the U.S.[60] Rockefeller had already become a millionaire ($1 million is equivalent to $26 million[38] in 2019 dollars).[61]

He instinctively realized that orderliness would only proceed from centralized control of large aggregations of plant and capital, with the one aim of an orderly flow of products from the producer to the consumer. That orderly, economic, efficient flow is what we now, many years later, call ‘vertical integration‘ I do not know whether Mr. Rockefeller ever used the word ‘integration’. I only know he conceived the idea.

— A Standard Oil of Ohio successor of Rockefeller [54]

Carnegie Steel Company:

Carnegie made his fortune in the steel industry, controlling the most extensive integrated iron and steel operations ever owned by an individual in the United States. One of his two great innovations was in the cheap and efficient mass production of steel by adopting and adapting the Bessemer process, which allowed the high carbon content of pig iron to be burnt away in a controlled and rapid way during steel production. Steel prices dropped as a result, and Bessemer steel was rapidly adopted for rails; however, it was not suitable for buildings and bridges.[35]

The second was in his vertical integration of all suppliers of raw materials. In the late 1880s, Carnegie Steel was the largest manufacturer of pig iron, steel rails, and coke in the world, with a capacity to produce approximately 2,000 tons of pig metal per day. In 1883, Carnegie bought the rival Homestead Steel Works, which included an extensive plant served by tributary coal and iron fields, a 425-mile (684 km) long railway, and a line of lake steamships.[28] Carnegie combined his assets and those of his associates in 1892 with the launching of the Carnegie Steel Company.[36]

Vertical Integration:

In microeconomics and management, vertical integration is an arrangement in which the supply chain of a company is owned by that company. Usually each member of the supply chain produces a different product or (market-specific) service, and the products combine to satisfy a common need.

…

Vertical integration has also described management styles that bring large portions of the supply chain not only under a common ownership but also into one corporation (as in the 1920s when the Ford River Rouge Complex began making much of its own steel rather than buying it from suppliers).

Second, and more interestingly, is that Whole Foods has a strong private label business with its 365 brand. Why is this important to Amazon? In case you haven’t noticed, Amazon is becoming more and more vertically integrated. It now runs eight private brand lines of fashion apparel, including Lark & Ro, Ella Moon and Mae, and this business has been growing rapidly. The online giant also offers private brand products for everything from batteries to baby wipes and diapers. Amazon is even developing its own content. Its “Manchester by the Sea” film was produced completely by Amazon and was a blockbuster hit last year.

The typical argument for vertical integration is that private brand product is higher margin than third-party branded product. That is true and is an important part of Amazon’s strategy. But even more important is the fact that private brand product represents differentiation. In a retail market where there is a “sea of sameness” and national brands can be found through nearly every channel, private and exclusive brands create a reason for the consumer to buy through Amazon as opposed to going elsewhere. If Amazon has the best shopping experience, the fastest delivery, the best prices, and now unique products, why would you shop anywhere else?

Horizontal Integration

Horizontal integration is the process of a company increasing production of goods or services at the same part of the supply chain. A company may do this via internal expansion, acquisition or merger

Facebook and Instagram

One of the most definitive examples of horizontal integration was Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram in 2012 for a reported $1 billion. Both Facebook and Instagram operated in the same industry (social media) and shared similar production stages in their photo-sharing services. Facebook sought to strengthen its position in the social sharing space and saw the acquisition of Instagram as an opportunity to grow its market share, reduce competition, and gain access to new audiences. Facebook realized all of these through its acquisition. Instagram is now owned by Facebook but still operates independently as its own social media platform.

Horizontal integration can allow companies to quickly expand their reach and expertise while reducing costs. (+)

Ecosystems are the new oil

packet.com/blog/ecosystems-are-the-new-oil/

hbr.org/1993/05/predators-and-prey-a-new-ecology-of-competition

Step outside the tech world (where we are comfortable using the word in a very narrow sense) and you’ll recall from primary school science that ecosystems are much bigger concepts. A series of highly interdependent elements, functioning together symbiotically to enable the lifecycle.

Much like the magnificently complex geological ecosystem that provides for life on our planet, end-to-end technology ecosystems are nuanced, crazy hard to create, and fragile. They require time, meticulous effort, and patience to create. When you’re collecting GitHub stars instead of mineral rights, you have to consistently add value, show accountability, and demonstrate stewardship. Otherwise those stars quickly lose their brightness.

Ways your company can support and sustain open source

via Chris Aniszcyk [CTO of Cloud Native Computing Foundation]

The success of open source continues to grow; surveys show that the majority of companies use some form of open source, 99% of enterprises see open source as important, and almost half of developers are contributing back.

It’s important to note that companies aren’t contributing to open source for purely altruistic reasons. Recent research from Harvard shows that open source-contributing companies capture up to 100% more productive value from open source than companies that do not contribute back.

Matt’s comments:

If you’re using open source software at your company, then this software could be considered in economics terms as a “complement” to your company’s product, where its availability, quality, and ecosystem directly bolsters it.

Here, Joel Spolsky writes on how smart companies in the past have strategized to further their business interests by supporting complements to their products, or otherwise “commoditizing their complements” to great results

(Joel on Software) Hitting the high notes:

joelonsoftware.com/2005/07/25/hitting-the-high-notes/

So, why isn’t there room in the software industry for a low cost provider, someone who uses the cheapest programmers available? (Remind me to ask Quark how that whole fire-everybody-and-hire-low-cost-replacements plan is working.)

Here’s why: duplication of software is free. That means that the cost of programmers is spread out over all the copies of the software you sell. With software, you can improve quality without adding to the incremental cost of each unit sold.

…The same thing applies to the entertainment industry. It’s worth hiring Brad Pitt for your latest blockbuster movie, even though he demands a high salary, because that salary can be divided by all the millions of people who see the movie solely because Brad is so damn hot. …

Five Antonio Salieris won’t produce Mozart’s Requiem. Ever. Not if they work for 100 years.

Five Jim Davis’s — creator of that unfunny cartoon cat, where 20% of the jokes are about how Monday sucks and the rest are about how much the cat likes lasagna (and those are the punchlines!) … five Jim Davis’s could spend the rest of their lives writing comedy and never, ever produce the Soup Nazi episode of Seinfeld.

Matt’s note: while Joel’s perspective here is a bit extreme, it does raise an important point. I think it’s dangerous to start thinking so narrowly though.

Mozarts are great, but often that’s not all it takes for high performing teams and businesses. This can mean diversity, and also different types of contributors.

In the book Peopleware for instance, an example was given of a worker who had a strange track record that the projects they were on were less likely to fail than the average. They worked to make the projects they worked on “fun” for team members, and were able to rally and get people interested in the projects.

This type of contribution wouldn’t have been measurable with performance metrics (see Econ 101), but was still a significant contribution to the team goal (see identity management method)

(Joel Spolsky) finding great developers

What doesn’t happen, and I guarantee this, what never happens is that you say, “wow, this person is brilliant! We must have them!” In fact you can go through thousands of resumes, assuming you know how to read resumes, which is not easy, and I’ll get to that on Friday, but you can go through thousands of job applications and quite frankly never see a great software developer. Not a one.

Here is why this happens. The great software developers, indeed, the best people in every field, are quite simply never on the market.

(Paul Graham) Great Hackers

After software, the most important tool to a hacker is probably his office. Big companies think the function of office space is to express rank. But hackers use their offices for more than that: they use their office as a place to think in. And if you’re a technology company, their thoughts are your product. So making hackers work in a noisy, distracting environment is like having a paint factory where the air is full of soot.

Several friends mentioned hackers’ ability to concentrate– their ability, as one put it, to “tune out everything outside their own heads.” I’ve certainly noticed this. And I’ve heard several hackers say that after drinking even half a beer they can’t program at all. So maybe hacking does require some special ability to focus. Perhaps great hackers can load a large amount of context into their head, so that when they look at a line of code, they see not just that line but the whole program around it. John McPhee wrote that Bill Bradley’s success as a basketball player was due partly to his extraordinary peripheral vision…

This could explain the disconnect over cubicles. Maybe the people in charge of facilities, not having any concentration to shatter, have no idea that working in a cubicle feels to a hacker like having one’s brain in a blender. (Whereas Bill, if the rumors of autism are true, knows all too well.)

One big company that understands what hackers need is Microsoft. I once saw a recruiting ad for Microsoft with a big picture of a door. Work for us, the premise was, and we’ll give you a place to work where you can actually get work done.

And you know, Microsoft is remarkable among big companies in that they are able to develop software in house. Not well, perhaps, but well enough.

Companies like Cisco are proud that everyone there has a cubicle, even the CEO. But they’re not so advanced as they think; obviously they still view office space as a badge of rank. Note too that Cisco is famous for doing very little product development in house. They get new technology by buying the startups that created it– where presumably the hackers did have somewhere quiet to work.

In a low-tech society you don’t see much variation in productivity. If you have a tribe of nomads collecting sticks for a fire, how much more productive is the best stick gatherer going to be than the worst? A factor of two? Whereas when you hand people a complex tool like a computer, the variation in what they can do with it is enormous.

That’s not a new idea. Fred Brooks wrote about it in 1974, and the study he quoted was published in 1968. But I think he underestimated the variation between programmers. He wrote about productivity in lines of code: the best programmers can solve a given problem in a tenth the time. But what if the problem isn’t given? In programming, as in many fields, the hard part isn’t solving problems, but deciding what problems to solve. Imagination is hard to measure, but in practice it dominates the kind of productivity that’s measured in lines of code.

Productivity varies in any field, but there are few in which it varies so much. The variation between programmers is so great that it becomes a difference in kind. I don’t think this is something intrinsic to programming, though. In every field, technology magnifies differences in productivity. I think what’s happening in programming is just that we have a lot of technological leverage. But in every field the lever is getting longer, so the variation we see is something that more and more fields will see as time goes on. And the success of companies, and countries, will depend increasingly on how they deal with it.

Interesting

Along with good tools, hackers want interesting projects. What makes a project interesting? Well, obviously overtly sexy applications like stealth planes or special effects software would be interesting to work on. But any application can be interesting if it poses novel technical challenges. So it’s hard to predict which problems hackers will like, because some become interesting only when the people working on them discover a new kind of solution. Before ITA (who wrote the software inside Orbitz), the people working on airline fare searches probably thought it was one of the most boring applications imaginable. But ITA made it interesting by redefining the problem in a more ambitious way.

I think the same thing happened at Google. When Google was founded, the conventional wisdom among the so-called portals was that search was boring and unimportant. But the guys at Google didn’t think search was boring, and that’s why they do it so well.

This is an area where managers can make a difference. Like a parent saying to a child, I bet you can’t clean up your whole room in ten minutes, a good manager can sometimes redefine a problem as a more interesting one.

… Along with interesting problems, what good hackers like is other good hackers. Great hackers tend to clump together– sometimes spectacularly so, as at Xerox Parc. So you won’t attract good hackers in linear proportion to how good an environment you create for them. The tendency to clump means it’s more like the square of the environment. So it’s winner take all. At any given time, there are only about ten or twenty places where hackers most want to work, and if you aren’t one of them, you won’t just have fewer great hackers, you’ll have zero.

Having great hackers is not, by itself, enough to make a company successful. It works well for Google and ITA, which are two of the hot spots right now, but it didn’t help Thinking Machines or Xerox. Sun had a good run for a while, but their business model is a down elevator. In that situation, even the best hackers can’t save you.

I think, though, that all other things being equal, a company that can attract great hackers will have a huge advantage. There are people who would disagree with this. When we were making the rounds of venture capital firms in the 1990s, several told us that software companies didn’t win by writing great software, but through brand, and dominating channels, and doing the right deals.

They really seemed to believe this, and I think I know why. I think what a lot of VCs are looking for, at least unconsciously, is the next Microsoft. And of course if Microsoft is your model, you shouldn’t be looking for companies that hope to win by writing great software. But VCs are mistaken to look for the next Microsoft, because no startup can be the next Microsoft unless some other company is prepared to bend over at just the right moment and be the next IBM.

…It’s a mistake to use Microsoft as a model, because their whole culture derives from that one lucky break. Microsoft is a bad data point. If you throw them out, you find that good products do tend to win in the market. What VCs should be looking for is the next Apple, or the next Google. I think Bill Gates knows this. What worries him about Google is not the power of their brand, but the fact that they have better hackers.

Harvard Business Review – Stop Hiring for Culture Fit

Via Patty McCord, former Chief Talent Officer of Netflix (+)

Extra: NPR’s All Things Considered interviews Patty McCord: How the Architect of Netflix’s Innovative Culture Lost Her Job to the System

Finding the right people is also not a matter of “culture fit.” What most people really mean when they say someone is a good fit culturally is that he or she is someone they’d like to have a beer with. But people with all sorts of personalities can be great at the job you need done. This misguided hiring strategy can also contribute to a company’s lack of diversity, since very often the people we enjoy hanging out with have backgrounds much like our own.

Making great hires is about recognizing great matches—and often they’re not what you’d expect. Take Anthony Park. On paper he wasn’t a slam dunk for a Silicon Valley company. He was working at an Arizona bank, where he was a “programmer,” not a “software developer.” And he was a pretty buttoned up guy.

A few months later I sat in on a meeting of his team. Everyone was arguing until Anthony suddenly said, “Can I speak now?” The room went silent, because Anthony didn’t say much, but when he did speak, it was something really smart—something that would make us all wonder, Damn it, why didn’t I think of that? Now Anthony is a vice president. He’s proof that organizations can adapt to many people’s styles.

Once you’ve made an offer and hired someone, you need to keep assessing compensation. I learned this during a period when Netflix was losing people because of exorbitant offers from our competitors. One day I heard that Google had offered one of our folks almost twice his current pay, and I hit the roof. He was a really important guy, so his manager wanted to counter. I got into a heated e-mail exchange with his manager and a couple of VPs. I wrote, “Google shouldn’t decide the salaries for everybody just because they have more money than God!” We bickered for days. They kept telling me, “You don’t understand how good he is!” I was having none of it.

But I woke up one morning and thought, Oh, of course! No wonder Google wants him. They’re right! He had been working on some incredibly valuable personalization technology, and very few people in the world had his expertise. I realized that his work with us had given him a whole new market value. I fired off another e-mail: “I was wrong, and by the way, I went through the P&L, and we can double the salaries of everybody on this team.” That experience changed how we thought about compensation. We realized that for some jobs we were creating expertise and scarcity, and rigidly adhering to internal salary ranges could harm our best contributors, who could make more elsewhere. We decided we didn’t want a system in which people had to leave to be paid what they were worth. We also encouraged our employees to interview elsewhere regularly. That was the most reliable and efficient way to learn how competitive our pay was.

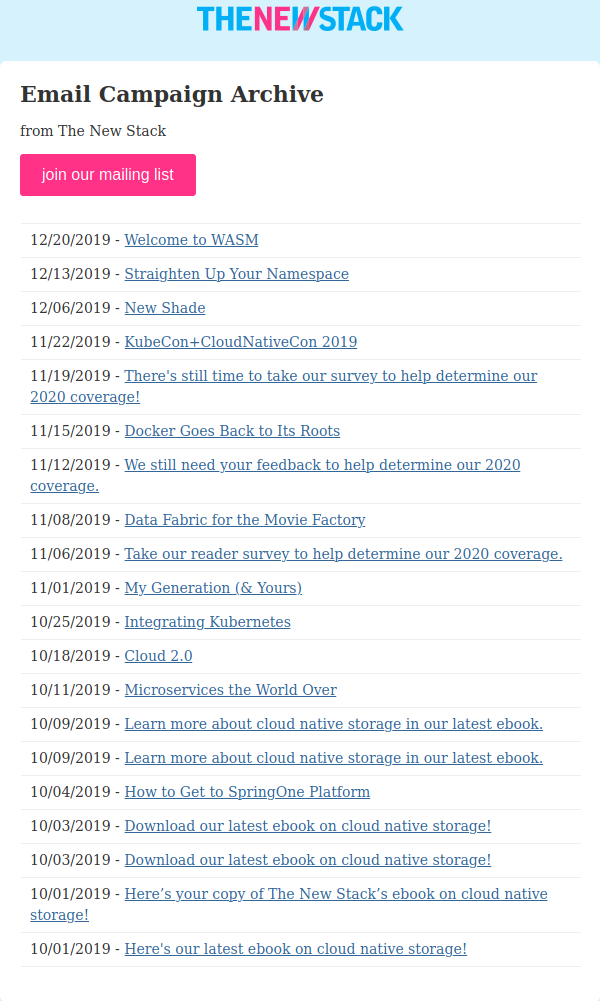

The New Stack (Architecture, Kubernetes, modern software architecture):

thenewstack.io/newsletter-archive

Data and business:

The Guardian email-newsletters

The Wall Street Journal

Glassdoor Economic Research

(analysis of economic and BLS data, economic insights based on data obtained from Glassdoor’s platform, and other analysis)

Seeking alpha newsletter:

https://seekingalpha.com/account/user_settings

Previously:

![]()